Technology and elaborate storytelling have made opening and closing ceremonies increasingly grand. After the extravaganzas of Beijing, Vancouver and London, can Sochi go to new levels?

Published in the January 31, 2014 issue of The Globe and Mail

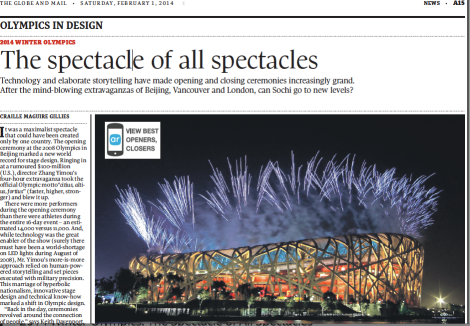

It was a maximalist spectacle that could have been created only by one country. The opening ceremony at the 2008 Olympics in Beijing marked a new world record for stage design. Ringing in at a rumoured $100-million (U.S.), director Zhang Yimou’s four-hour extravaganza took the official Olympic motto “citius, altius, fortius” (faster, higher, stronger) and blew it up.

There were more performers during the opening ceremony than there were athletes during the entire 16-day event – an estimated 14,000 versus 11,000. And, while technology was the great enabler of the show (surely there must have been a world-shortage on LED lights during August of 2008), Mr. Yimou’s more-is-more approach relied on human-powered storytelling and set pieces executed with military precision. This marriage of hyperbolic nationalism, innovative stage design and technical know-how marked a shift in Olympic design.

“Back in the day, ceremonies revolved around the connection of people,” says Keith Davenport, who was director of the opening ceremony at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi before leaving to take over the top role at the Toronto 2015 Pan Am/Parapan Am Games. “We still have that connection, but it’s also about how we tell the story, rather than just putting people into the mix of where the ceremony is.”

Mr. Davenport has worked on four Olympics, and says that technological advances in the past decade have enabled human-powered innovation in stage design. Automated projection can draw viewers’ attention anywhere in the stadium, giving designers the space and flexibility to string together an endless montage of spectacular stagecraft. “Drama created in the ceremony is above you, below you and in the middle of the field of play,” he says. In Beijing, 44,000 LED pixels on the floor of the stadium lit up in the shape of 10-metre Olympic rings, which 20 performers, dressed as glowing angels, swooped down and appeared to lift up.

Or consider director Danny Boyle’s eccentric Britfest at the London 2012 Games, which featured a tribute to the National Health Service and actor Kenneth Branagh as the 19th-century engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, proudly surveying the dawn of the Industrial Revolution – complete with life-sized smokestacks rising from the field of play. “Shifting from the green and pleasant land scene to this one was one of the most awe-inspiring moments of the Games,” Mr. Davenport says. “Thousands of people executed a flawless sea change that could have gone so wrong. That wasn’t technical – it was all manpower.”

The Olympics have always been as much about spectacle as they are about sport. As The Naked Olympics author Tony Perrottet notes, the ancient Greeks staged a “total pagan entertainment package.” Along with javelin-throwing competitions and chariot races, there were palm readers and fire-eaters.

The Olympics are still a five-ring circus. Today, increasingly sophisticated ceremonies allow a host country to project its own self-image to billions of people – often nostalgically quirky (a flying Mary Poppins fighting an inflatable Lord Voldemort at London 2012), charmingly over the top (Beijing 2008, all of it), or downright folksy (dancing trolls at the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer). Where else could you watch the Queen skydive into the Olympic stadium with James Bond, aka Daniel Craig? Or a giant glowing polar bear, as at the 2010 Winter Games in Vancouver?

Even in Beijing, which had a 147-metre scroll that unfurled to tell 5,000 years of Chinese history and innovative technical monitoring codes to track the thousands of performers, it wasn’t just the high-tech stagecraft that awed spectators. “The most amazing thing was the sheer poetry of a performance that was human-driven,” says architect Ray Winkler, director of the British event production company Stufish Entertainment Architects, which worked on the opening ceremony at the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin and on the Beijing event. “The high point of the show wasn’t really the man flying overhead or things coming out of the floor, but the massive synchronicity of thousands of drummers, or a three-dimensional Tetris based on human interaction. Without good design intent behind it, you can’t present the show. Technology can’t be the tail that wags the dog.”

Much of the behind-the-scenes wizardry in Beijing is credited to Mr. Winkler’s former business partner, legendary concert creator Mark Fisher, who designed concerts for some of the biggest names in music, including Pink Floyd, the Rolling Stones and Lady Gaga before his death in 2013. Mr. Fisher was a senior designer on Beijing.

“Consider the trajectory of the stadium tour, like the Beatles at Shea Stadium in 1965,” Mr. Winkler says. “It was probably nothing more than a scaffolding deck. Now look at something like U2’s 360° tour in 2010, which required 120 semis [transport trucks] to drive it around the world. The complexity has exploded into the stratosphere.”

Increasingly, producers look to technology to enable previously impossible feats of creativity. At the Vancouver Games in 2010, Spinifex Group designed three-dimensional killer whales that appeared to swim across the floor of the stadium. It was just a preview of what may come as screens get bigger and sharper, says Kim Gavin, creative director of the London 2012 closing ceremony and one of Britain’s leading stage designers. This kind of augmented reality was put to great effect at the Beijing Games when performers embedded within pixels became human-sized pieces of movable type (to illustrate a Chinese invention). Performers made giant waves and yin-yang symbols with their bodies and, in a touch that was a little on the nose, formed the Chinese characters for He, or harmony, during pauses.

Mr. Boyle tried his own hand at augmented reality in 2012. “Danny wanted to project a certain image around the crowd, which led to what we called audience pixels,” Mr. Gavin says. “It meant that each of the 80,000 seats was a pixel in what became a huge TV screen. It was a massive lighting tool.”

Like the Games themselves, the ceremonies are a kind of competition, as hosts try to top the spectacles of their predecessors. The creatives behind the ceremonies in Sochi, such as long-time Olympic production company Five Currents, has been tight-lipped on what to expect, but if the venue is any indication it may be a show to rival London and Beijing. Sochi is the first Olympics to have its own dedicated venue, the Fabergé egg-inspired Fisht Stadium. (Mr. Gavin’s team had to practise in a parking lot and got keys to the London stadium only at midnight on the day before the show.)

As Mr. Davenport says: “The days of the audience kit, when you give everybody a seat-specific coloured poncho, are over.”